Black Sea Grain Initiative & facilitating Russian agricultural exports

Alongside the Black Sea Grain Initiative, which facilitated exports from three Ukrainian ports, a separate “Memorandum of Understanding” was signed between Russia and the UN to facilitate the unimpeded export of Russian agricultural products and fertilizers. This represented a dual-track approach to mediation that aimed to appeal to both parties’ interests.

The two agreements:

• Brokered by Turkey and the UN, the Black Sea Grain Initiative aimed to “facilitate the safe navigation for the export of grain and related foodstuffs and fertilizers, including ammonia from the Ports of Odesa, Chernomorsk, and Yuzhny”. A joint coordination and inspection centre was established in Istanbul – staffed by officials from Ukraine, Russia, Turkey, and the UN. Reflecting the state of hostilities, Ukraine and Russia signed parallel but identical “mirror” documents on July 22, 2022.

• In addition, Russia signed a Memorandum of Understanding with the UN Secretariat, which sought to “facilitate the unimpeded access to global markets for food and fertilizers, including the raw materials required to produce fertilizers (including ammonia), originating from the Russian Federation”. While the grain deal lasted for 120 days (with the possibility of extension), the memorandum had a shelf life of three years.

Why did it fall apart?

• Russia allowed the deal to expire on July 17, 2023, having threatened to withdraw many times before and suspending its participation for a few days in October 2022. The Kremlin claimed that “hidden” Western sanctions were hindering Russia’s food and fertilizer exports, thus contravening the terms of the memorandum.

• According to the International Crisis Group, the memorandum’s contents “does not guarantee that Western powers will drop measures complicating Russian exports”, since “the UN cannot compel other states to cease these measures”, even if “the commitment to use its diplomatic capabilities in this case is significant”. Crucially, while “the memorandum does not spell out what will happen if Russia is unsatisfied with the UN’s progress... there is an implicit understanding that Moscow could feel less committed to the Black Sea deal if its own exports do not get to market”.

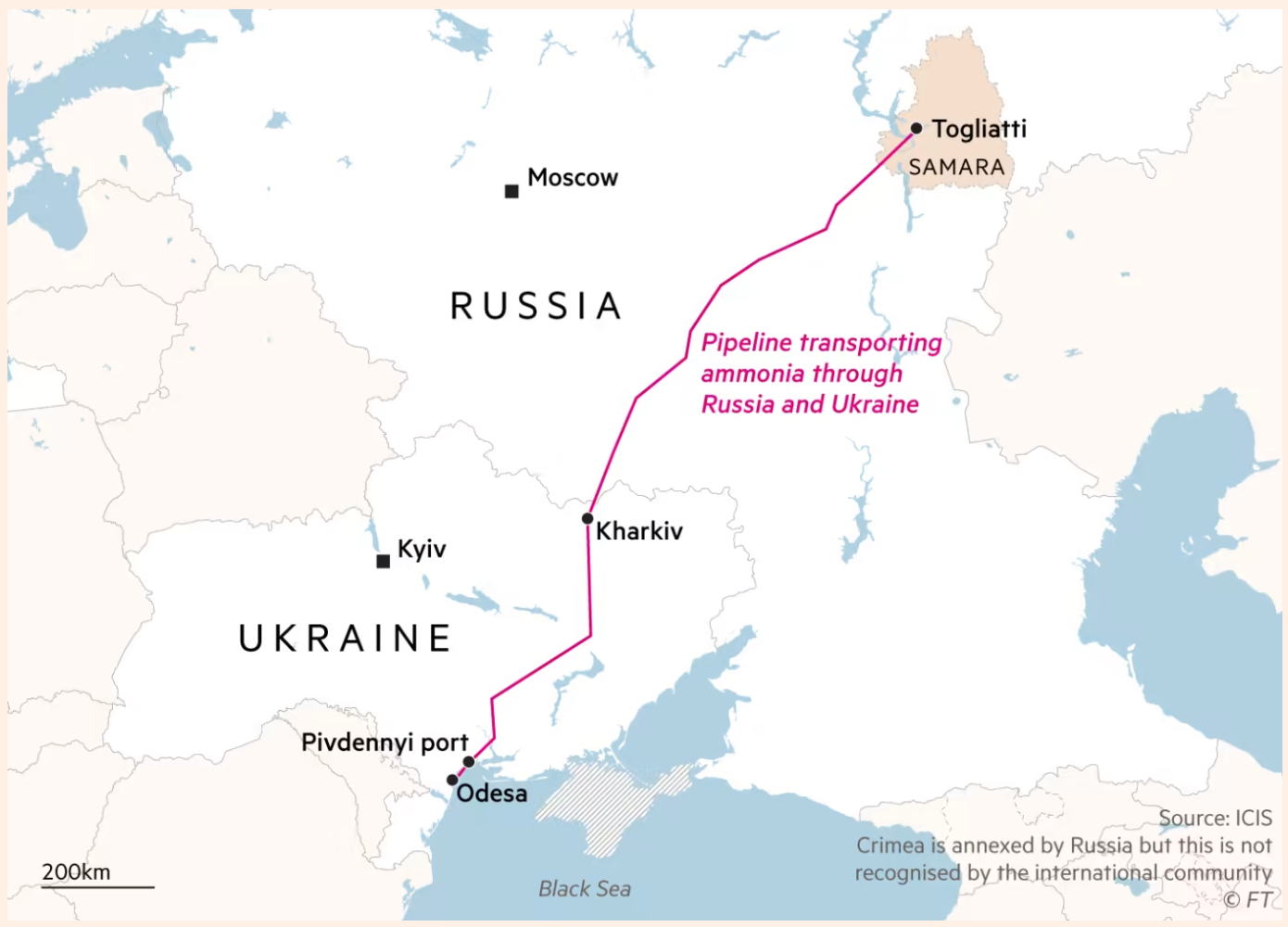

• In a letter to UN officials in March 2023, Moscow insisted that Rosselkhozbank, the state agricultural bank, be reconnected with the SWIFT banking system. It also wanted to restart the Togliatti-Odesa ammonia pipeline, which ran south through to Ukraine’s Pivdennyi Port and used to pump up to 2.5m tonnes annually of Russian ammonia before being shut down in the wake of the February 2022 invasion. Other demands included the resumption of Western supplies of agricultural machinery and parts; the lifting of restrictions on maritime insurance; providing access to ports for Russian ships and cargo; and unblocking the assets and accounts of Russian fertilizer companies. The failure to make progress on these “systematic objectives” of the memorandum was cited as a key reason for Russia’s withdrawal from the Black Sea Grain Initiative.

Did Russian complaints about “hidden” sanctions have a point?

• Putin’s decision to quit the Black Sea Grain Initiative was met with widespread disapproval in the West. Putin was accused of “playing a cynical game” and using the deal “to soften sanctions on Russia more generally”. Yet the International Crisis Group argues that for the Kremlin, despite its humanitarian rhetoric, this was precisely the point of the initiative.

• Neither the US nor the EU sanctioned exports of Russian food and fertilizer. But “Russian companies… repeatedly complained that Western banks, insurance providers and shipping companies still refuse[d] to work with them, for fearing of overstepping the boundaries of the exemptions or of attracting bad publicity”. As a workaround, the UN proposed Rosselkhozbank form a subsidiary in Luxembourg that could be connected to SWIFT, while JP Morgan began processing some Russian grain export payments at the request of the US government in the meantime. This was dismissed by the Russian Foreign Ministry as a “deliberately unworkable” idea that would take many months to set up.

• And while Russian grain exports for the 2022/23 season reached a new high (due to record shipments to Saudi Arabia), its exports of anhydrous ammonia (AA) saw a dramatic reduction, hampered by the closure of the Togliatti-Odesa pipeline. Moscow pressed for the resumption of shipments through the pipeline, pointing out that the transit of ammonia, “although not spelled out literally, is implied by the logic of the agreement”. It was supported in this endeavour by the UN, which proposed a two-part deal: the Russian fertilizer company Uralchem would ship its ammonia gas to the Ukrainian border, where it would be purchased by US-headquartered commodities trader Trammo. Kyiv, however, would only consider allowing Russian ammonia to transit its territory in exchange for broadening the grain deal to include more Ukrainian ports and a wider range of commodities. In May 2023, Russia began restricting registrations at Pivdennyi port due to the ongoing disputes over the ammonia pipeline.