The “47th parallel”

How to secure Ukraine’s border, and bring down European energy prices while we’re at it...

February 20, 2025

A plan to secure Ukraine’s border – without the US picking up the tab.

Any demarcation line will be eight times the length of Korea’s. (Korea’s demilitarized zone runs 150 miles. Ukraine and Russia share a border approximately 1,282 miles. And, arguably, Ukraine’s 674-mile border with Belarus ought to be secured as well.)

Who are the peacekeeping troops to do it?

Cartographically incorrect, but what will surely now come to be referred to as the “47th parallel” between Ukraine and Russia is going to require a lot of peacekeepers.

The border ought to be managed by United Nations peacekeepers (not Western troops or EU peacekeepers). This is the only remedy that’s likely to be accepted by Russia. And the conflict does need Russia’s sign-off to stop the killing and get wrapped up.

UN troops are capable of steadying the situation, and will not be seen as a provocation. While the UK and France are fully committed to Ukraine’s future defense, drop rhetoric of British and French troops being stationed in Ukraine (which has a much sturdier home military than the Republic of Korea in 1953) – the suggestion of their presence potentially scuppering US attempts at expedient resolution (as well as not being terribly well received at home).

How many peacekeepers would be needed?

“People, ideas, machines – in that order!” - Colonel John Boyd

The person to put forward a zero-bloat troop number and configuration is Erik Prince. The founder of Blackwater (the “Prigozhin of America”, as a mutual friend memorably described him), Erik is a figure highly respected by the US top team. And many consider Erik to have had the best, cost-effective plan for Afghanistan, that the Pentagon did not pick up – which President Trump reportedly personally regrets from his first term.

A border plan from Erik, for Ukraine, with a Presidential rubber stamp (or Sharpie signature), then to be funded the following way…

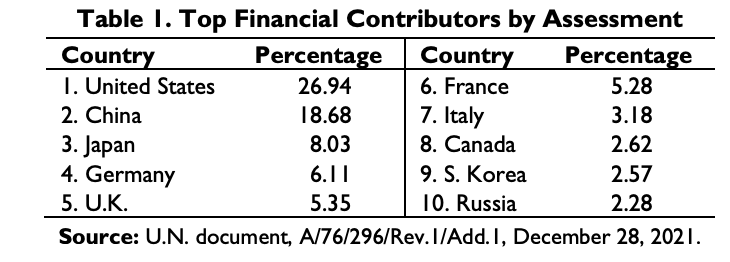

How to finance UN peacekeepers

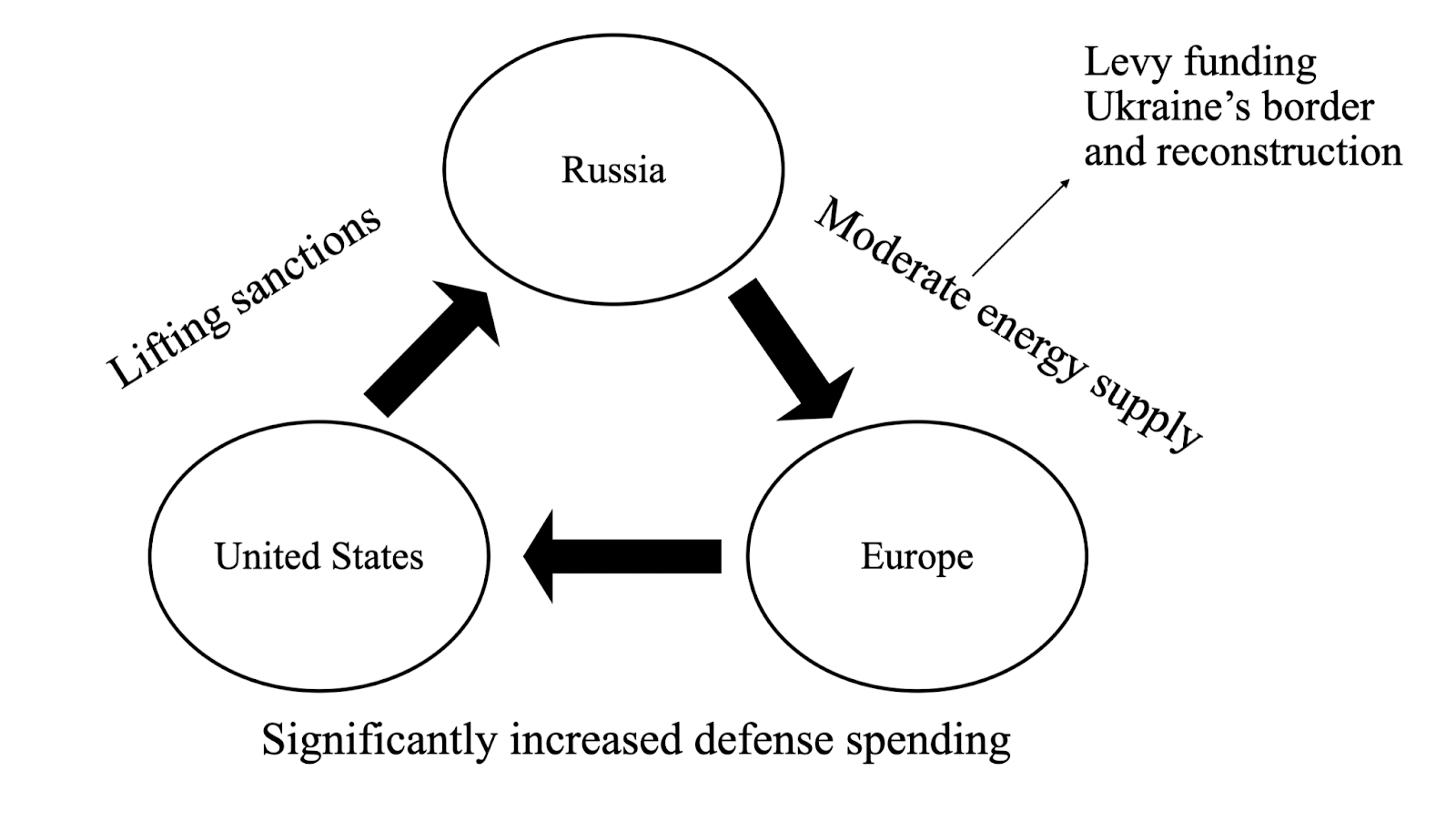

Thankfully, the President’s Ukraine Envoy, Lt. General Kellogg, has the answer. In his America First Policy Institute report of April 2024, co-authored with Fred Fleitz: “We also call for placing levies on Russian energy sales to pay for Ukrainian reconstruction.” Why not extend this idea to fund peacekeeping troops?

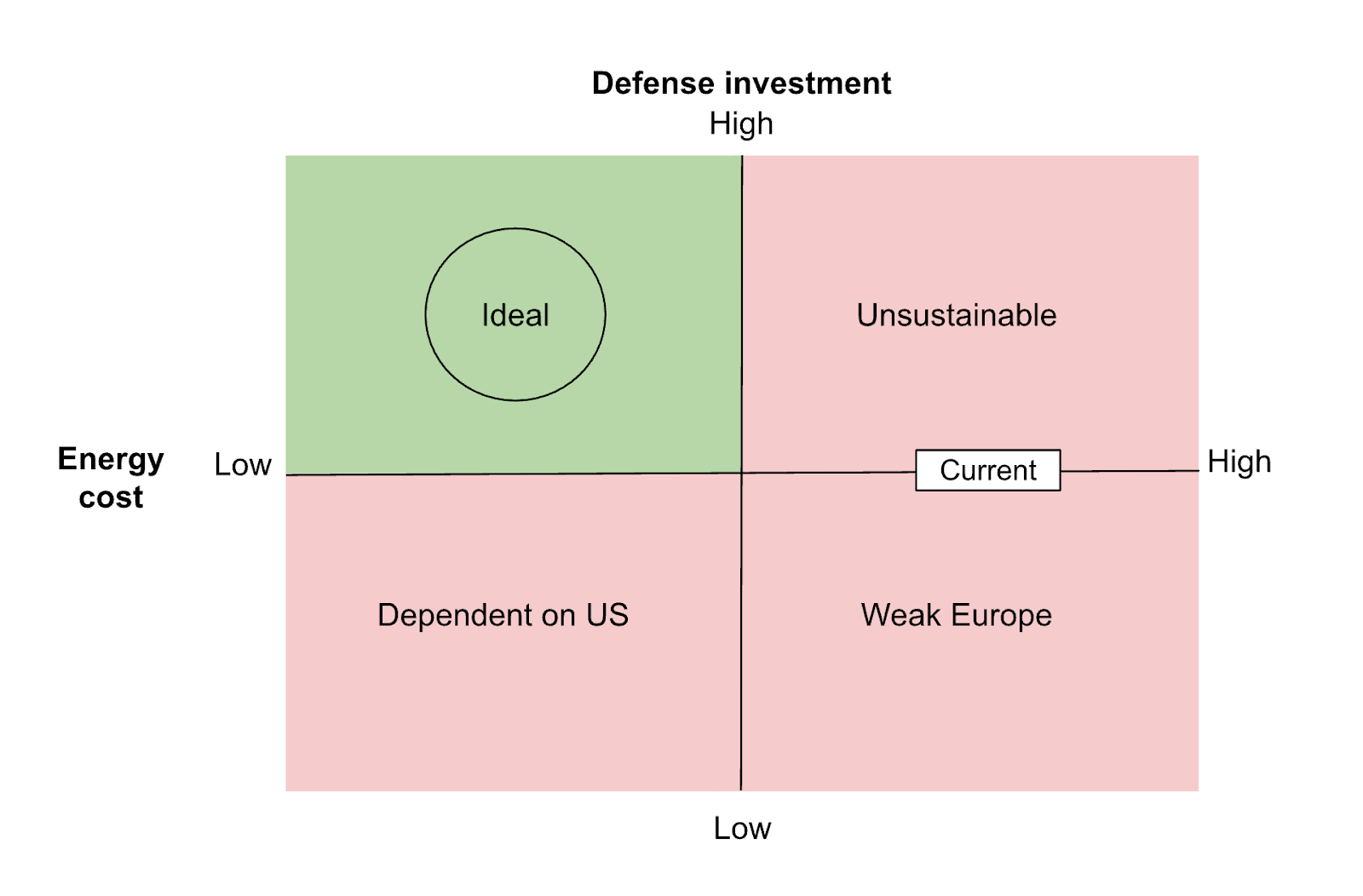

Europe ought to repair and restart one set of Nord Stream pipelines, and a moderate supply of Russian energy (which President Trump, in his first term, was on board with) could finance Ukraine’s neutral peacekeepers – discharging talk of “a deal with the devil”, as European media presently puts it.

A sensible amount of Russian energy supply with a levy would bring down European energy costs, keep American LNG prices competitive, and help bring down the recent uptick in US inflation.

European natural gas prices are roughly four times higher than the United States’s. It can be made known that the US will not get European countries to spend 2.5%+ on defense sustainably (as is needed) without Europe having cheaper, diversified energy supply.

A four-way bargain:

Europe resuming a responsible amount of Russian energy paying for Ukraine’s defense and reconstruction.

“Diversified, secure, affordable” (for Europe)

The US might, in short order, look to prioritise less of its natural gas for European export. Post-Stargate and DeepSeek, the US could need more of its energy at home to power its Manhattan Project-level build out of AI data centres. Ukraine’s peacekeeping force thus “Administered by the United Nations; specially funded by a levy on responsible Russian energy flows to Europe”.

How much can a levy on Nord Stream 1 raise?

We’ll leave to brainiacs – suggesting the likes of Bismarck Analysis – to crunch the numbers. They are better equipped to compile a comprehensive proposal: what price should a levy be set at, and how much could it raise?

To mere diplomatic wordcels like us, ChatGPT-4 suggests it’s a lot. And in the spirit of 20th century European deal-making:

“All the time I’ve known him, he’s gone for the essence of the problem... ‘Well yes, yes, there are all sorts of details that have got to be sorted out, but don’t we agree that this is really the main issue with which we’ve got to wrestle? And if we agree on that, then we can get all sorts of experts to work out the details... You must tell them: what is the essential, where do you want to get to, and then they can work out how to do it.” - Edward Heath, British Prime Minister 1970–1974, on Jean Monnet, one of the founding fathers of the European Union

Also, to bear in mind:

“The European Peace Facility is a fund worth over €17 billion financed outside the EU budget for a period of seven years (2021–2027), with a single mechanism to finance all actions under the Common Foreign and Security Policy in military and defence areas.”

There is an existing mechanism for the EU to specially provide UN funding. Proudly advertised on an EU web-page: “EU cooperation with the United Nations; Peace operations and crisis management”.

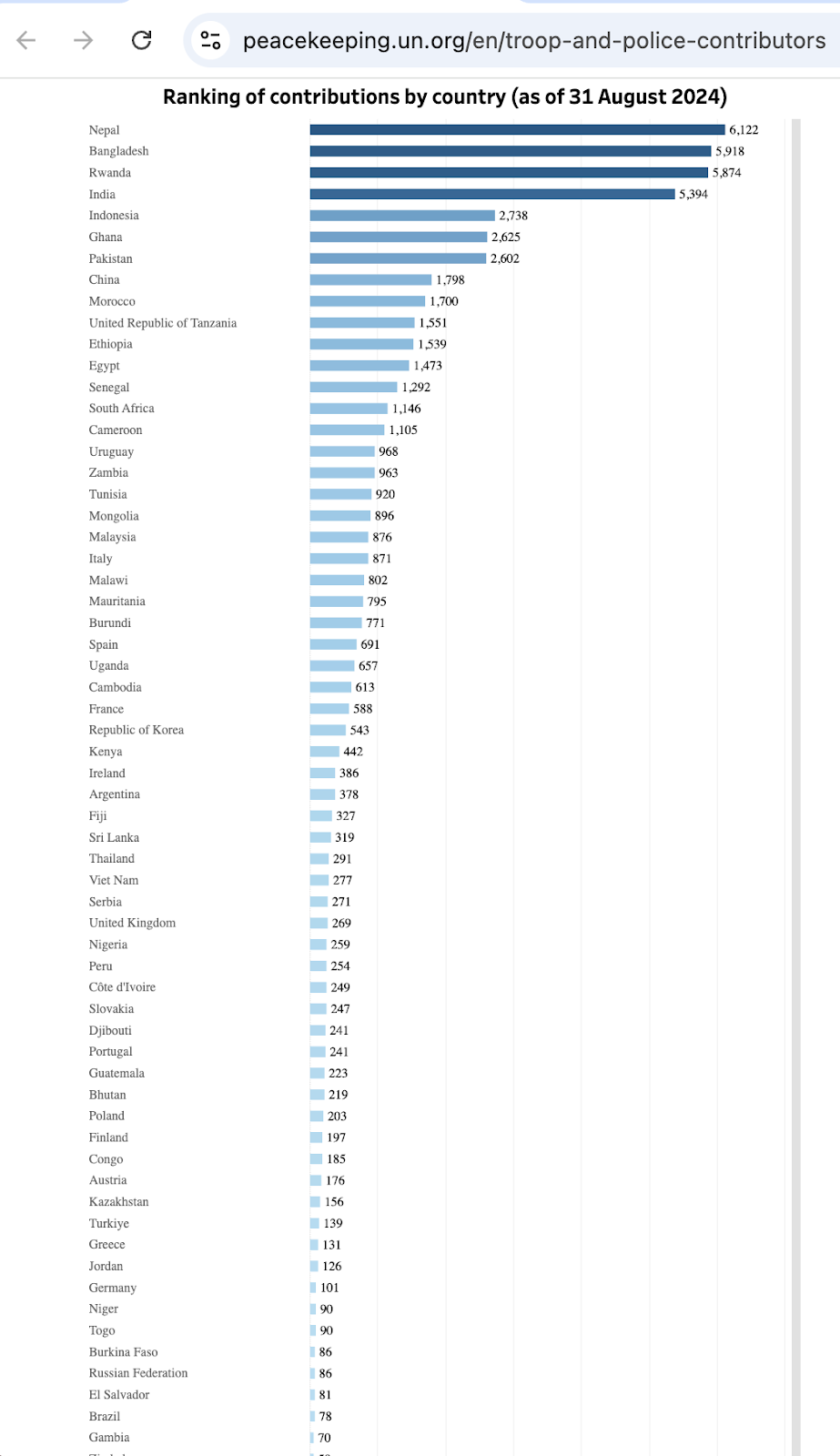

Who are UN peacekeepers? Where do they come from?

The first time I looked into this, I was surprised:

I’m not entirely sure what I was expecting, but I don’t think it was this.

Reading into the history of how this came to be:

“Since the late 1990s, when even traditional peacekeeping became more dangerous, industrialized countries have been unwilling to send their own personnel where risks are high and national interests low. Therefore, the West makes use of what could be described as ‘hired help’ from the Global South.

...There are three main explanations why countries from the Global South have contributed to UN peace operations: regional cooperation; recognition and prestige; and financial benefits.

Regional interests help to explain why African countries have provided, since 2013, the majority of troops on the continent with the most armed conflict and most peacekeepers.”

Other border measures

[*] Emulate Poland’s “East Shield”:

“Poland is already preparing for its [Ukraine’s] collapse. In recent months, Warsaw has been digging an anti-tank ditch along its border with Russia and Belarus – and has decided to extend it to Ukraine. The 400-mile-long ‘East Shield’ will almost double in size and include minefields and bunkers, anti-drone systems and AI-powered defences to protect Poland from possible invasion. Donald Tusk called the £2.5 billion project an ‘investment in peace’ to deter and discourage any possible aggressor.” - The Spectator, December 6, 2024

If Poland, as one country, can itself do 400 miles, can the EU, with a €17 billion “Peace Facility” fund manage 1,200–1,950 miles (including Poland’s help – using its same contractors)?

[*] Revive the Open Skies Treaty:

A dedicated, concise write up on this here: https://listeningto.org/Ukraine/Open-Skies/

In very brief: a revived treaty would provide the Baltic countries much better visibility of troop build-ups in Russia, and much better early-warning of any planned attack. Russian troop build-ups were visible (for the February 2022 invasion) as early as November 2021, and some in the crow’s nest of X were tweeting about it – but hardly anyone in the UK (besides Dominic Cummings) took the warnings seriously.

Though it was the first Trump administration that pulled out of the agreement, President Trump and then-Secretary Pompeo left the door open in 2020: “There’s a chance we may make a new agreement or do something to put that agreement back together.” Russia has signalled it would welcome this.

These ingredients, together, would make for a secure and affordable border.

Edward M. Druce is a former 10 Downing Street Special Advisor, having worked with the Chief Advisor to the Prime Minister, 2020–21.

This piece was put together with immense help from Sang-Hwa Lee and Catherine Hervieu.

Enjoy this article? We’re a small team of twenty- and early thirty-somethings who want to take on Foreign Affairs and do diplomatic journalism better. Read about this publication’s founding mission here. And if you like what we’re doing, please consider subscribing (free) for updates.